Interpretable machine learning¶

What is machine learning?¶

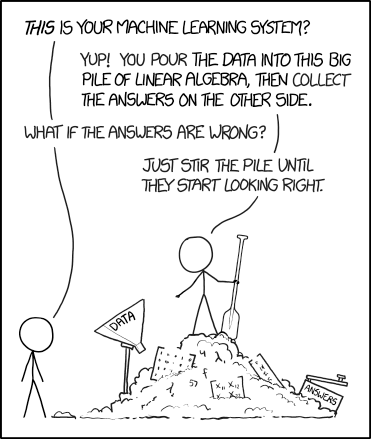

Machine learning is a set of methods that computers use to make and improve predictions or behaviors based on data.

For example, to predict the value of a house, the computer would learn patterns from past house sales.

We are going to focus on supervised machine learning. The goal of supervised learning is to learn a predictive model that maps features of the data (e.g. house size, location, floor type, …) to an output (e.g. house price). If the output is categorical, the task is called classification, and if it is numerical, it is called regression. The machine learning algorithm learns a model by estimating parameters (like weights) or learning structures (like trees). The algorithm is guided by a score or loss function that is minimized. In the house value example, the machine minimizes the difference between the estimated house price and the predicted price. A fully trained machine learning model can then be used to make predictions for new instances.

Machines surpass humans in many tasks, such as playing chess (or more recently Go) or predicting the weather. Even if the machine is as good as a human or a bit worse at a task, there remain great advantages in terms of speed, reproducibility and scaling. A once implemented machine learning model can complete a task much faster than humans, reliably delivers consistent results and can be copied infinitely. Replicating a machine learning model on another machine is fast and cheap. The training of a human for a task can take decades (especially when they are young) and is very costly. A major disadvantage of using machine learning is that insights about the data and the task the machine solves is hidden in increasingly complex models. You need millions of numbers to describe a deep neural network, and there is no way to understand the model in its entirety. Other models, such as the random forest, consist of hundreds of decision trees that “vote” for predictions. To understand how the decision was made, you would have to look into the votes and structures of each of the hundreds of trees. That just does not work no matter how clever you are or how good your working memory is. The best performing models are often blends of several models (also called ensembles) that cannot be interpreted, even if each single model could be interpreted. If you focus only on performance, you will automatically get more and more opaque models.

Interpretability¶

When it comes to predictive modeling, you have to make a trade-off: Do you just want to know what is being predicted? For example, the probability that a customer will churn or how effective some drug will be for a patient.

Or do you want to know why the prediction was made and possibly pay for the interpretability with a drop in predictive performance? In some cases, you do not care why a decision was made, it is enough to know that the predictive performance on a test dataset was good. But in other cases, knowing the ‘why’ can help you learn more about the problem, the data and the reason why a model might fail.

Interpretability methods are classified in:

- Intrinsic: limit the complexity of the model (decision trees for example)

- Post hoc: apply methods to analyse the model after training (permutation feature importance for example). These can also be appled to intrinsicallt interpretable methods.

The interpretation methods can be differentiated according to their results:

- Feature summary statistic: Many interpretation methods provide summary statistics for each feature. Some methods return a single number per feature, such as feature importance, or a more complex result, such as the pairwise feature interaction strengths, which consist of a number for each feature pair.

- Feature summary visualization: ost of the feature summary statistics can also be visualized. Some feature summaries are actually only meaningful if they are visualized and a table would be a wrong choice.

- Model internals: The interpretation of intrinsically interpretable models falls into this category. Examples are the weights in linear models or the learned tree structure (the features and thresholds used for the splits) of decision trees.

- Data point: This category includes all methods that return data points (already existent or newly created) to make a model interpretable.One method is called counterfactual explanations. To explain the prediction of a data instance, the method finds a similar data point by changing some of the features for which the predicted outcome changes in a relevant way (e.g. a flip in the predicted class).

Linear regression, logistic regression, and decision trees are commonly used interpretable models.